Installing and Setting up Git

Chances are, you already have git running on your computer or you at least have heard of Git before. For this training, you will need to setup git locally and know few basics about git.

Table of Contents

- Installing Git

- Forking a Repository to your Account

- Cloning the Repository to your Machine

- Creating a new Branch for your repo

- Staging your Changes for a Commit

- Committing your Changes

- Pushing your new Branch to Your Fork on GitHub

Installing Git

If you don’t have Git installed, navigate to the official Git Download page and download it.

Getting Git for Mac

There are several ways to install Git on a Mac. You can choose from one of the following ways:

1) If you want a more up to date version, you can also install it via a binary installer. An OSX Git installer is maintained and available for download at the Git website, at http://git-scm.com/download/mac.

2) If you already have Homebrew, you can install Git by executing:

$ brew install git

Make sure you update your $PATH environment variable to include the latest install path of Git. For example:

$ echo 'export PATH="/usr/local/bin:/usr/local/sbin:~/bin:$PATH"' >> ~/.bash_profile

3) If you don’t mind registering an Apple developer account, then install the Xcode Command Line Tools. Go to connect.apple.com and register an Apple Developer account. Once you’ve registered, go to developer.apple.com/xcode, then click on “View downloads” and finding the appropriate command line tools for your version of OS X in the list. When your download finishes, go ahead and open the DMG. Run the Command Line Tools installer. On Mavericks (10.9) or above you can do this simply by trying to run git from the Terminal the very first time. If you don’t have it installed already, it will prompt you to install it.

Getting Git for Windows

If you’re already using Chocolatey or Windows 10’s package manager to install software, you can simply run the following command from an elevated Powerbash (right click, select ‘Run as Administrator’):

$ cinst git.install

$ cinst poshgit

# Restart PowerShell / CMDer before moving on - or run

$ env:Path = [System.Environment]::GetEnvironmentVariable("Path","Machine") + ";" + [System.Environment]::GetEnvironmentVariable("Path","User")

$ cinst git-credential-winstore

$ cinst githubVerifying Git Installation

Now that you have Git installed, open up PowerShell on Windows or terminal on Mac. If everything worked correctly, you should be able to run git --version.

Signing up for a Free GitHub account

Before we can get started, you need to register with GitHub for a free account. Either create or login into your account on GitHub.

Forking a Repository to your Account

Now you are ready to do more with Git. Let’s start with a sample project. Head over to the devopsfun repo on GitHub repository and click the little ‘fork’ button in the upper right.

This will create a copy of the repository as it exists in the original account into your own account.

Cloning the Repository to Your Machine

Visit your fork (which should be at github.com/{your_github_username}/devopsfun) and copy the “HTTPS Clone URL”. Using this URL, you’re able to clone the repository, which downloads the whole repository, including its history and information about its origin locally. From PowerShell on Windows or terminal on Mac, change into the directory where you would like to clone your repo.

Clone the code to your local machine.

$ git clone https://github.com/{your_github_username}/devopsfunThis should generate output that looks roughly like this:

$ git clone https://github.com/{your_github_username}/devopsfun

Cloning into 'devopsfun'...

...

...

Checking connectivity... done.You can run explorer . from PowerShell on Windows or open . from Terminal on Mac to open up the folder in Explorer or Finder respectively. All the files are there - including the history of the whole repository. The connection to your fork ({your_github_username}/devopsfun) is still there.

Creating a new Branch for your repo

In modern Git development, every single change that you want to make to the code base will be made in a “branch”. Like a tree branch, the branch is “based” on a different branch, and unlike other SCM systems, Git branches are very lightweight. In our case, your base branch is gh-pages. The default branch name for GitHub repositories is master. In order to create a new branch, you can always run:

# This makes sure that your new branch is based on master

$ git checkout gh-pages

# When the default branch of a repo is "master", you should "git checout master" instead

# The below command creates a new branch

$ git checkout -b my-new-branchYou can now go ahead and make your changes - adding files, writing code, fixing bugs. Keep in mind that a branch should host isolated changes. For example, you should create one branch that fixes a bug, then another branch for to develop a new feature you want to implement.

Staging your Changes for a Commit

Now that you made your changes, you can “stage” them for a commit. Whenever you stage a file for a commit, you make a snapshot of the file at the time you’re staging it for a commit. If you change a file after you staged it, you will have to stage it again. To stage a file, simply run:

$ git add ./path-to/my-file.mdIf you just want to stage all files in your current repository (including deletions), run:

$ git add --all .Committing your Changes

Now that your changes have been staged, we’re ready to commit them. You can either pass the commit command a title for your commit - or omit the parameter, in which case Git will open up the default text editor for you to create a commit message.

To commit the quick way:

$ git commit -m "Add new feature: Git is Awesome"To commit the long way, allowing you to define both title and message of your commit:

$ git commitPushing your new Branch to Your Fork on GitHub

Let’s say you have implemented a new feature, made some changes, committed the changes - now we have to make sure that your changes also end up on GitHub. To do so, we have to push your local branch to your fork on GitHub. Run the command below, using the name of the branch you want to push to

$ git checkout NAME_OF_YOUR_NEW_BRANCH

$ git push -u origin NAME_OF_YOUR_NEW_BRANCHBonus: Making a Pull Request

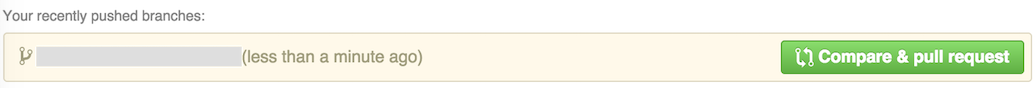

Now, head over to the devopsfun repository. In most cases, GitHub will pick up on the fact that you just pushed a branch with some changes to your local fork. The Compare & pull request button will appear in case you want to push those changes to the upstream repo.

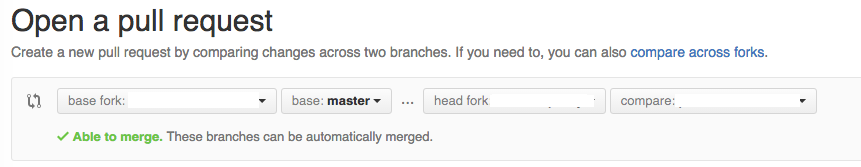

After you have clicked the Compare & pull request button, GitHub will open up the ‘Create a Pull Request Page’. It is a good idea to list the feature you have created or the bug you have fixed by referencing an issue #.

As soon as you hit the Create Pull Request button, it’ll show up in the list of pull requests.

Bonus: Updating Pull Requests

Once people have reviewed your pull request, it is very likely that you want to update it. Whenever you update the branch in your fork, your pull request will be automatically updated.

Let’s look at a scenario: You just pushed your branch (using git push -u origin NAME_OF_YOUR_BRANCH), went to GitHub, and created a Pull Request.

To update the PR with additional changes, edit your files in your branch - then, commit the changes and push them to GitHub:

$ git checkout NAME_OF_YOUR_BRANCH

# Make changes, stage all changes for commit

$ git add --all .

# Commit

$ git commit

# Push to GitHub

$ git pushIf you want to update your Pull Request without creating a new commit, you can “amend” your last commit. To do so, call git commit with the --amend parameter and force-push the result to GitHub, overwriting the previous version.

$ git checkout NAME_OF_YOUR_BRANCH

# Make changes, stage all changes for commit

$ git add --all .

# Commit

$ git commit --amend

# Push to GitHub

$ git push -fBonus: Squashing Commits

Commit often is a great practice to backup in case you mess up. At the same time, you don’t want your pull request to contain all your commit history. In general, a pull request should contain one commit to keep upstream project clean. For that to happen, we need to rewrite history.

Rewriting Git history is a bit scary, but it’s easy to do. Let’s say you just made 3 commits to your branch. Before making a pull request, you want all those commits to be turned into one. To change the history of your last six commits, run:

$ git rebase -i HEAD~3It is important that you change only commits that you made, since your branch will not be compatible with “upstream” if you rewrite history that is already present in the repository there. You can however mess with your own fork as much as you want to, since you should be the only person working with it.

Once you run the command, you will be presented with a screen that looks like this:

pick 9kdkp92 Update main.js

pick e84j8k1 Optimize controller

pick 48kiro9 Error checking for edge casesNote that every single commit begins with the word pick, followed by its commit id and the commit message. You can replace the word pick with one of the options below:

p,pick: use commitr,reword: use commit, but edit the commit messagee,edit: use commit, but stop for amendings,squash: use commit, but meld into previous commitf,fixup: like “squash”, but discard this commit’s log messagex,exec: run command (the rest of the line) using bash

In order to squash all 3 commits into the very first one you made, you would change the file to:

pick 9kdkp92 Update main.js

fixup e84j8k1 Optimize controller

fixup 48kiro9 Error checking for edge casesThen, once you’re done, update the branch on your own fork in GitHub. Push with the f parameter (force) to tell Git to overwrite whatever GitHub has in the branch:

$ git push -fIf this is the first time you are pushing to this branch, then use the normal push command - no need to overwrite with the f paramter.

$ git push -u origin NAME_OF_YOUR_BRANCHBonus: Syncing Your Fork

After some time, you’ll find that your fork has become out of sync with the upstream repository (as others add features and bug fixes and they get merged in). To keep your fork in sync, you just need to do a local rebase and then push those changes. There are few different ways to do this, but this is one that helps you rebase when syncing with the latest from upstream:

# Make sure you're on default branch of the repo - maybe master, for our sample repo it is gh-pages

$ git checkout gh-pages

# Get all of the latest from upstream default branch - master or gh-pages in our case

$ git pull upstream gh-pages

# Push latest from local default branch to remote default branch

$ git push origin gh-pages

# Checkout your own branch

$ git checkout NAME_OF_YOUR_BRANCH

# Rebase in the changes from upstream default branch to your feature branch

$ git rebase gh-pages

# And then push those to your feature branch on your fork on GitHub

$ git push -f origin NAME_OF_YOUR_BRANCH